It was the best of times, it was the worst of times; it was the age of grunge, it was the age of Robin Hood ballads; it was the epoch of flannel, it was the epoch of tight rolled jeans; it was the season of techno, it was the season of boy-band pop; it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair; we had everything before us, we had nothing before us . . .

Yep. It was the early ’90s. And I was in high school.

What this meant for me was a whole lot of awkwardness; some purposely bad hair (read: mullet) as a reaction to small-town high school snobbery; punk, grunge, and techno music; and some incredibly bad emotive poetry. Oh…and Latin. And Dungeons and Dragons. And cross-country running. And folk wrestling (i.e. collegiate). And Tae Kwon Do. And skateboarding. And street skating. And flannel. And Chuck Ts. And massively over-sized overalls. Really, just pure nerdery and hormones and more awkwardness.

And angst. Holy crow, the angst.

Oh, man. It was horrible.

The 1990s were actually a pretty incredible time, though. Music had diverged in two important ways that created somewhat overlapping, but dramatically different constituents. Grunge music was as a wake-up call to pop-radio consumers. Techno, trance, house, and drum and bass music flooded the warehouses, farm fields, and clubs in the Midwest along with what, at that time, was a very forward-thinking, optimistic social movement packaged within rave culture.

So, with my eyes opening to capitalism and social repression through grunge and punk and my heart opening to the promise of Hakim Bey’s Temporary Autonomous Zones that the rave community was enthralled by, I took my first high school career placement test on a fancy, dirty white computer that generally just ran Oregon Trail and Scorched Earth.

This test was exciting. I pictured a pat on my back by our counselor as the computer screen was flashing that I was a perfect fit as either an archaeologist or a writer. Needless to say, it was a total shock to me when the first career fit was proctologist.

Okay, so it didn’t actually say “you should be a proctologist,” but that was the first option in the program’s list of what I would be good at. Now, I don’t want to upset any proctologists. Honestly, you all are awesome and deserve far more credit than you can possibly ever receive, but as a 16-year-old romantic . . . well, let’s just say there was a cognitive disconnect.

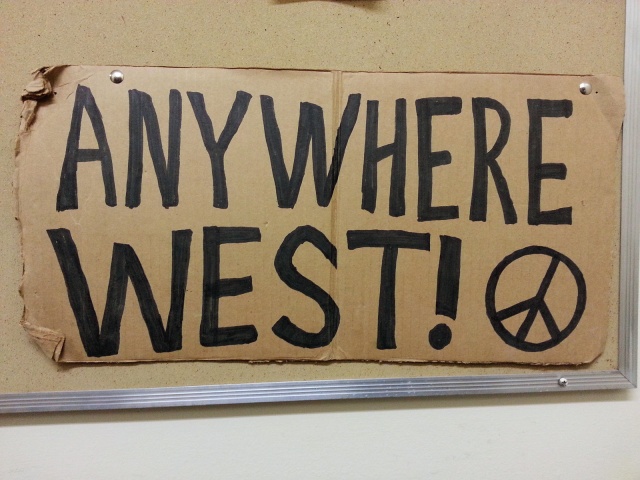

Clearly, this test is faulty. I should take it again, right? Right. This second time will surely clear things up. Wait…what…bus driver? What the he–? This is about where my counselor walked over and patted me on the back. I got up and slouched out of the office, trying not to trip over my untied Chucks or the huge hem of my baggy overalls. I wrapped my flannel around me like a blanket and set about trying to understand how things could have gone so horribly wrong. Who was I supposed to be?

I still have no idea how those tests work. I’m guessing they were along the lines of an early Buzzfeed quiz. But there I was, apparently destined to be the first operator of a mobile proctology clinic. My solution to this was simple. Flee.

I promptly asked my mom if I could go to a high school archaeology field school. Note that I didn’t choose a writing camp. I can only imagine that, somewhere deep down, a part of me already recognized that lines like, “A tin puppet prepares his twin sorrows / he’ll force nature’s sign” were best forgotten with the other garbage in Al Capone’s vault.

So, off to archaeology camp I went, where I immediately learned far more about historic blue glass, rusted pieces of historic metal, and old pieces of wood than a high schooler who yearned for images of Western skies at dusk could handle. I was done. And not in any good way. Archaeology was horrible. And boring. Definitely. Not. The Bomb.

So, I trudged through the last bit of high school. Graduated and ended up chasing down the writing dream. I put together two mostly horrible novels that I still tell myself I might salvage one-day, a slew of trite and tripe short stories, and more bad poetry than an entire decade of an Introduction to Poetry class could possibly create. I wasn’t a total failure. I did have a couple of poems published and, for a while, there were some bites on my first novel—but I spent more time at the bar than the typewriter, and I never really had my heart in the effort of it. Writing was hard. Drinking was not.

The years blew by. Weird experiences and amazing people (and vice versa) racked up like points in a particularly great pinball game. And before I knew it, I’d put the fiction writing on hold, packed up my heart, said good bye to those amazing people, and moved out to the great American desert. In Albuquerque, after a year of racking up some more points on that odd pinball machine, I landed at the University of New Mexico. There, I started taking anthropology classes and eventually took an Introduction to Archaeology class taught by Dr. Patricia Crown.

School was always pretty easy for me. Minimal effort, maximum return. Then I took Patty’s class. The first test in that 100-level class was a brick to the face. Somehow, I rallied, buckled down, and poured myself into my studies in a way I never really had before. I had to fight against a lifetime of education that had taught me that “smart” should mean “gets it right away” and not “worked at it till it was learned.” But, somehow, I did it, and came out of that class with the first A I’d ever really been proud of. There would be many more that I would fully earn, but that was the first. During that semester, I finally put my hand to the plow, and I’ve been tilling ever since.

Now, there are some other things we could talk about, but I’m getting short on time and am way over the word limit (as always). So, for now, we’ll summarize and discuss.

Life handed me a bus-driving proctologist. I said no way to archaeology. I tried to shoot the moon for writing, but eventually found my way back to archaeology. There, I fell in love with humanity’s detritus. And even more importantly, I fell in love with the sense of humanity you can get from studying the things we love.

Now I get tears in my eyes when I see my daughter’s favorite teddy bear slowly getting older from 6 years of intense love. I choke up when I hear my youngest tell me she’s worried about how damaged her favorite stuffed toy is and that she doesn’t want her friends to see it, but then she still finds her and snuggles with her at night. I do this because I know that as inanimate as these things are, they’re defining my daughters as much as my wife and I are. These things form the spaces within which my children grow, and learn, and become amazing. These things create the shape of who they are and will be as young women and will continue to create the spaces that shape them until they die. And I know that long after I’m gone, things of mine will remain that will preserve a portion of the shape of who I was. Our things are our stories and they are us. And this is exciting and comforting to me.

So…how I became an archaeologist is maybe not the most interesting tale, and it’s definitely not the culmination of a single-minded lifelong quest. Instead, I think it is more the chronicle of this long process of moving from making up stories to realizing that there was already a world littered with stories.

After writing this out, it now seems clear that how I became an archaeologist is also why I became an archaeologist: because I realized that archaeology is an honest way to uncover the story of the people I love. Archaeology holds the story of all of the people I’ve learned so much from. It holds the story of my wife and my children, my family and my friends. All of the incredible, and horrible, people I’ve met, along with millennia of incredible people I could not meet. Because archaeology, once we get past the dictionary definition, is not the study of things, it’s the study of the human narrative and of our humanity. It’s the study of our stories that form in and around our things.

Basically, dear reader, I became an archaeologist because I think you are pretty darn awesome. You and all of your things that make you, you. And I would really like to read that story.

A version of this essay originally appeared on Archaeology Southwest’s blog as one of many blogs about how archaeologists ended up working in our discipline: https://www.archaeologysouthwest.org/2015/10/12/how-bad-poetry-can-lead-to-a-career-in-archaeology/

I loved this! You are a wonderful storyteller! You seem to have picked a perfect vocation based on the why you shared and your love of people. So glad to have found your site.

Jordan

LikeLike

Thank you so much, Jordan! That means a lot. I quite enjoy what I do. I’m really glad that I can transmit a bit of that excitement to folks.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This was a great read! My high school never made us do aptitude tests, now I kind of wish it had.

LikeLike

Haha. Those things. I think they just had a randomizer program with a useless quiz as a front-end. And thank you!

LikeLike

I’m so intrigued by your story! This was an awesome read. I love all the nostalgia from the 90’s. I love how much you love us. That all resonated with me. Thank you!!

LikeLike

Thanks so much, digupthedreamer! It was fun to live and to write. I’m glad this resonated with you. 🤠

LikeLike